Research Process - Overview

It's a good idea to keep detailed research notes throughout the process. This can often save lots of time in the end. You may want to use a tool to manage your citations and save your sources as you research, Zotero can help you do this.

Step 1: Identify your topic

Read more

Some questions to get you started

- With what topics are you already familiar?

- In what topics do you have a genuine interest?

- In what topics do you already have a strong opinion; positive or negative

- Before diving into your topic, it might be helpful to understand key concepts like research frameworks and methodologies. Learn more about What is a Research Framework? and What is Research Methodology? to guide your approach.

Still can't think of a topic?

Consider:

- Brainstorming; write down any ideas that come to mind

- Talking with lecturers

- Talking with classmates

- Consulting sources like general and subject specific encyclopaedias (ahem, Wikipedia), handbooks, and textbooks for ideas

- Browsing recent issues of periodicals for current issues

Wikipedia: The Good and the Not So Good

Wikipedia is a great place to start your research, but not a great place to end it.

Strengths of Wikipedia

-

Wikipedia is updated frequently. New information can be, and often is, added to the site within minutes. Due to editorial limitations, scholarly encyclopaedias are usually updated annually.

-

Because Wikipedia crowd sourced, there is the potential for a broader authorship than is found in academic publications.

-

Citations in Wikipedia offer a wider array of materials, including articles and resources that are available for free and online.

Weaknesses of Wikipedia

-

Editors on Wikipedia are not necessarily experts. Authorship on Wikipedia is often anonymous or obscured.

-

Articles are always changing, making them difficult to cite in your research. An article you read today, may look quite different tomorrow.

-

Articles can be vandalised, providing wildly inaccurate information.

Review your assignment

Before you begin, make sure you understand your assignment and its requirements.

Consider:

- Length; How many words are required?

- Date Due; When is the paper due?

- Additional requirements; Are there any specific requirements for the assignment?

Step 2: Find background information

Read more

Use your textbook, class notes, reference books, Wikipedia, and/or a broad Google search to find information about the events, places, people and jargon associated with your topic.

- Identify keywords related to your topic.

- Search encyclopaedia and other general sources.

- Collect additional keywords that you can use to search later.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a great place to start your research, but not a great place to end it. Strengths of Wikipedia Wikipedia is updated frequently. New information can be, and often is, added to the site within minutes. Due to editorial limitations, scholarly encyclopaedias are usually updated annually. Because Wikipedia crowd sourced, there is the potential for a broader authorship than is found in academic publications. Citations in Wikipedia offer a wider array of materials, including articles and resources that are available for free and online. Weaknesses of Wikipedia Editors on Wikipedia are not necessarily experts. Authorship on Wikipedia is often anonymous or obscured. Articles are always changing, making them difficult to cite in your research. An article you read today, may look quite different tomorrow. Articles can be vandalised, providing wildly inaccurate information.Wikipedia: The Good and the Not So Good

Step 3: Sources

Step 3.1: Search for your sources

Read more

See Where to find sources and How to search

Think of it like a healthy diet. You want a variety of high quality sources going into your research.

Store your sources in Zotero as you go. This will save you a lot of time and help prevent accidental plagiarism.

Step 3.2: Evaluate what you’ve found

Read more

Once you have a variety of sources (or as you're collecting them), it's time to evaluate them. There are several models and checklists for guiding researchers through the evaluation process, but all are asking the same questions.

ABC Checklist

Accuracy: Is the information correct and current?

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work?

- If it's an online source, are the links working and up-to-date?

Bias: Is the information fair and objective?

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, to teach, to sell, to entertain?

- Do the authors or sponsors make their intention or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

Credibility: Is this source believable and trustworthy?

- Who is the author, publisher, source, or sponsor?

- What are the author's credentials or organisational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information such as a publisher or e-mail address?

- What kind of reputation does the author, publisher, or website have? Search the Internet to see what other credible sources have to say about the resource that you are evaluating.

If you can't find an author or organisation listed, especially on a website, you should move on and look for another source.

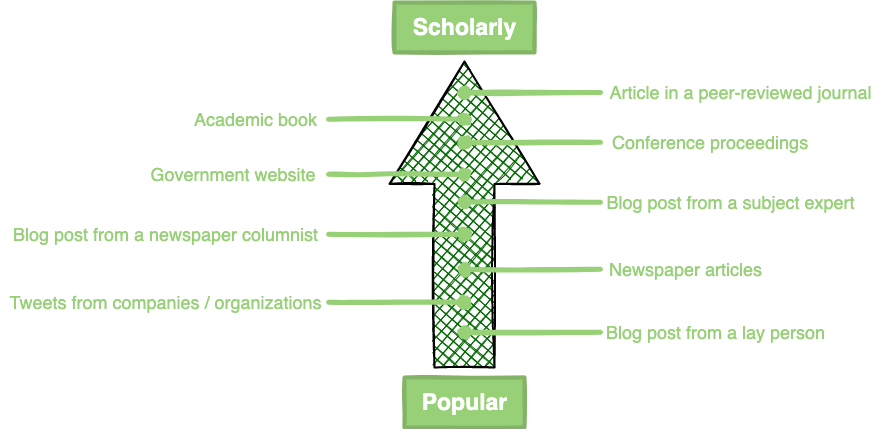

This diagram illustrates the concept of authority, placing a number of sources on the spectrum from popular to scholarly.

Adapted from My Learning Essentials resources developed by the University of Manchester Library and licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0.

Step 3.3: Make notes

Read more

While doing your research you will be making connections and synthesising what you are learning. Some people find it useful to make "idea cards" or notes in which they write out the ideas and perceptions they are developing about their topic.

How to Work with Notes

- After you take notes, re-read them.

- Then reorganise them by putting similar information together. Working with your notes involves re-grouping them by topic instead of by source. Re-group your notes by re-shuffling your index cards or by color-coding or using symbols to code notes in a notebook.

- Review the topics of your newly-grouped notes. If the topics do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly, you may need to do additional research or re-think your original research.

- During this process you may find that you have taken notes that do not answer your research question or support your working thesis directly. Don't be afraid to throw them away.

It may have struck you that you just read a lot of "re" words: re-read, reorganise, re-group, re-shuffle, re-think. That's right; working with your notes essentially means going back and reviewing how this "new" information fits with your own thoughts about the topic or issue of the research.

Grouping your notes should enable you to outline the major sections and then the paragraphs of your research paper.

Step 4 (if applicable): Compilation / Evaluation of Original Data

Read more

- For some research projects, you may have data that you have collected. Now is the time to compile and evaluate that data.

Step 5: Write your paper

Read more

Writing your paper is where you bring together all the research, analysis, and planning you've done so far. This step involves narrowing your topic into a focused research question, structuring your argument, integrating evidence effectively, and ensuring clarity and flow in your writing.

Additional Tips for Writing Success

- Start early—writing takes time to revise and refine.

- Break down writing into manageable tasks (e.g., draft one section at a time).

- Read aloud—this helps identify awkward phrasing or errors in flow.

- Seek feedback—ask peers or instructors to review drafts for clarity and coherence.

By following these steps, you can craft a well-organized paper that effectively communicates your research findings and arguments.

Step 5.1: Narrow Your Topic into a Research Question

Read more

- Refine your original topic into a clear, specific research question or thesis statement.

- Consider:

- Is the research question feasible within the available timeframe and resources?

- Is the question too broad or too narrow? Strike a balance to ensure depth without overwhelming scope.

- A well-crafted research question or thesis will guide the direction of your paper and help you stay focused.

Step 5.2: Structure Your Paper

Read more

A strong structure is essential for presenting your argument logically and persuasively. Most academic papers follow this general structure:

Introduction

- Introduce the topic and explain why it is important (exigence).

- Provide necessary background information to contextualize your research.

- Present your thesis statement—a concise summary of your main argument or research focus.

Body Paragraphs

- Divide the body into logical paragraphs, each focusing on one central idea.

- Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that introduces its theme.

- Develop the paragraph with evidence (e.g., data, quotes, examples) and explain how it supports your thesis.

- Use transitions to maintain logical flow between paragraphs and sections.

- Address counterarguments where relevant, demonstrating why they do not undermine your thesis.

Conclusion

- Summarize your main points and restate the significance of your argument.

- Revisit your thesis in light of the evidence provided but avoid introducing new information.

- Optionally, suggest areas for future research or implications of your findings.

Step 5.3: Integrate Sources Effectively

Read more

Research writing is a conversation between your ideas and those of others. Use sources to support, challenge, or contextualize your arguments while maintaining your own voice.

- Introduce: Briefly describe the source (e.g., author credentials, title) to provide context for its relevance.

- Integrate: Use direct quotes, paraphrases, or summaries as appropriate:

- Quotations emphasize credibility by using an author’s exact words.

- Paraphrasing highlights specific points in your own words.

- Summarizing condenses larger ideas into brief overviews.

- Connect: Explain how the source supports or relates to your argument.

- Cite: Give proper credit to authors using the required citation style (e.g., APA for FoB, Chicago for FoAD).

Step 5.4: Maintain Clarity and Flow

Read more

Effective academic writing is clear, concise, and logically organized:

- Signposting: Use words like "however," "therefore," "in contrast," or "moreover" to guide readers through transitions in ideas.

- Consistency: Stick with consistent terminology for key concepts throughout the paper to avoid confusion.

- Simplicity: Avoid overly complex sentences or jargon unless necessary; aim for precision and readability.

Step 5.5: Cite Your Sources (as You Write)

Read more

Proper citation ensures you give credit to authors whose work you reference:

- Citation is a cornerstone of scholarly communication and adds credibility to your work.

- Use citation management tools like Zotero to organize references and generate bibliographies efficiently.

For more information about citing and citations, see our guide on the topic.

Please note: FoB uses APA-style citations and FoAD uses Chicago-style citations.

Citing as you write saves a lot of time in the end! It is recommended to use Citation Management Software such as Zotero to store your sources and generate bibliographies.

Step 6: Proofread

Read more

The importance of proofreading cannot be understated.

Strategies to Help Identify Errors

- Work from a printout, not a computer screen. Besides sparing your eyes from the strain of glaring at a computer screen, proofreading from a printout allows you to easily skip around to where errors might have been repeated throughout the paper [e.g., misspelled name of a person].

- Read out loud. This is especially helpful for spotting run-on sentences and missing words, but you'll also hear other problems that you may not have identified while reading the text out loud. This will also help you adopt the role of the reader, thereby, helping you to understand the paper as your audience might.

- Use a ruler or blank sheet of paper to cover up the lines below the one you're reading. This technique keeps you from skipping over possible mistakes and allows you to deliberately pace yourself as you read through your paper.

- Circle or highlight every punctuation mark in your paper. This forces you to pay attention to each mark you used and to question its purpose in each sentence or paragraph. This is a particularly helpful strategy if you tend to misuse or overuse a punctuation mark, such as a comma or semi-colon.

- Use the search function of the computer to find mistakes. Using the search [find] feature of your word processor can help identify repeated errors faster. For example, if you overuse a phrase or use the same qualifier over and over again, you can do a search for those words or phrases and in each instance make a decision about whether to remove it or use a synonym.

- If you tend to make many mistakes, check separately for each kind of error, moving from the most to the least important, and following whatever technique works best for you to identify that kind of mistake. For instance, read through once [backwards, sentence by sentence] to check for fragments; read through again [forward] to be sure subjects and verbs agree, and again [perhaps using a computer search for "this," "it," and "they"] to trace pronouns to antecedents.

- End with using a computer spell checker or reading backwards word by word. Remember that a spell checker won't catch mistakes with homonyms [e.g., "they're," "their," "there"] or certain word-to-word typos [like typing "he" when you meant to write "the"]. The spell-checker function is not a substitute for carefully reviewing the text for errors.

- Leave yourself enough time. Since many errors are made and overlooked by speeding through writing and proofreading, setting aside the time to carefully review your writing will help you identify errors you might otherwise miss. Always read through your writing slowly. If you read through the paper at a normal speed, you won't give your eyes sufficient time to spot errors.

- Ask a friend to read your paper. Offer to proofread a friend's paper if they will review yours. Having another set of eyes look over your writing will often spot errors that you would have otherwise missed.